I appreciate a story that seeps into who I am, that makes unexpected connections, and in the process challenges me to recognise someone I would once have seen as ‘other’, says Judith Scully.

BY Judith Scully

Many moons ago, as a young nun I was introduced to daily spiritual reading, a mixture of lives of the saints, theology and spirituality ‘how-to’. The first left me discouraged and the remaining two contributed to my religious literacy. Books that nurtured my spirit, that took me into God-depths, were a gift to my middle years and beyond. The Shepherd’s Hut is one of those books, but you won’t find it in the spirituality section of any bookshop.

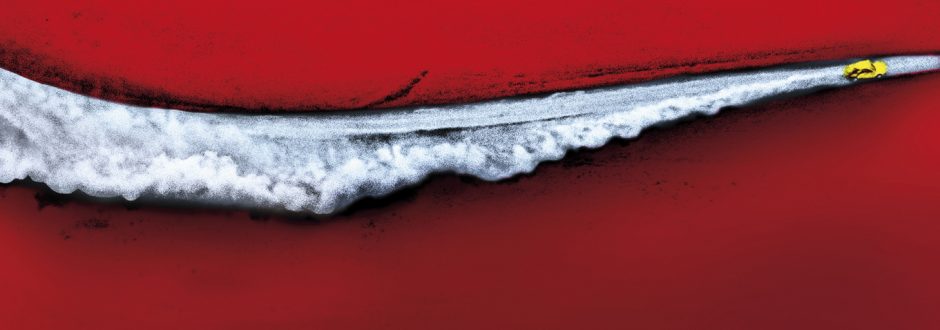

I picked it up because it was ‘the new Tim Winton’ and the review in the weekend paper hadn’t mentioned coastlines or the sea. I prefer my Winton dry and dusty, a coming to grips with Australia’s vast interior. Now, surrounded by aisles of Kmart’s latest must-haves, I read the first chapter – barely two pages long – a colloquial soliloquy, a speeding car, red dust flying, and every sentence lit through with a shaft of joy. I paid my money and left the store, and the little bubble of excitement that a new book promises was echoed by the spring in my step.

For me, choosing books usually involves cruising the shelves of a book shop or scanning the titles in the municipal library. Both leave me with a crick in my neck and a vague feeling of desperation. The cover might beckon and the title sharp enough to tease my interest, but if it fails the first chapter test, or sometimes even the first page, then it goes back on the shelf.

Some books are page-turners and tell an engrossing story, while others, like a good red wine, are better sipped slowly to let the flavor through. I appreciate a story that seeps into who I am, that makes unexpected connections, and in the process challenges me to recognise someone I would once have seen as ‘other’. And that’s how I met Jaxie.

Tim Winton wrote the book, Penguin Books published it and I bought it, but The Shepherd’s Hut is Jaxie’s story, written in his voice, his language, his experience of life. As I read page after page, I formed a picture of an adolescent, still in that in-between stage when face and voice are on a sliding scale between boy and man.

I am an old woman now and stories about adolescent boys have never been top of my must-read list. Gradually, and greatly to my surprise, Jaxie began teaching me something that life so far had failed to do – to appreciate teenage boys and never underestimate the effect that loving women can have on them. Even though nearly every page was flicked with violence, a fleeting and unexpected tenderness was tucked into Jaxie’s salty language when he talked about his mother, his nanna (I liked that bit because my grandsons call me nanna too) and Lee, his cousin and the love of his adolescent heart.

Jaxie’s father was a violent man and there was more of that at school, so when it culminated in tragedy it seemed almost predictable that he would take refuge in a landscape that was equally violent. For 40 or more pages Jaxie and I trudged across vast stubble paddocks and empty dry spaces, looking for shade trees, for signs of water. I listened to his memories of how things had been – might have been – feeling the grief in his loneliness, and marvelling at the depth of his thoughts, as though the emptiness of the land had cleared the way for him to voice his truth.

And that’s when Jaxie and I met Fintan MacGillis – and he was singing. What’s not to like about a man who sings to accompany the silence.

I knew Fintan was a hermit priest because I’d read a review – and now wished I hadn’t. In my imagination I had pictured him as a look-alike Thomas Merton – and of course he wasn’t. It would have been much more satisfying to discover that alongside Jaxie.

Part of me wanted to know his story, but the rest of me was content to sit on the sidelines and watch these two disparate characters find bits of themselves in each other. I knew enough about Jaxie to stand on the sidelines and cheer him on as he edged his way into his first positive male relationship.

They were age and youth, tip-toeing into private spaces, two loners negotiating their way through the niggling and explosions of togetherness into a peaceful silence. In fits and starts they talked – about priests, childhood memories, mothers, Jaxie’s nanna and Lee, now and again digging a little bit deeper into prickly matters, the kind that defy words, eventually getting to the big question – God.

The shepherd’s hut hid itself in a landscape that made no effort to soften its hard lines. It was a safe place for Jaxie and Fintan, somewhere to think and talk their way through to a point where there is only truth. As Fintan said, “Jaxie, you are an instrument of God”. Maybe Jaxie could say the same about Fintan.

Fintan was singing the first time I met him and he sang through the horror of his dying. That song found a place in Jaxie, and eventually he would learn to call it peace.