In this SPECIAL FEATURE, which includes a photo gallery, Debra Vermeer explores how Good Samaritan Colleges in Australia are providing educational environments that nurture indigenous students and empower them to realise their goals.

BY Debra Vermeer

Leaving her community of Borroloola in the Northern Territory at age 12 to undertake six years of boarding school at St Scholastica’s College in Sydney was a big challenge for Yanyuwa woman, journalist, politician and education advocate, Malarndirri McCarthy. But it was also an experience which she says shaped her future and opened up the world.

Malarndirri, who grew up between the communities of Borroloola and Alice Springs, is one of many indigenous women who have been educated at Good Samaritan Colleges over the decades, with about 136 students who identify as indigenous currently enrolled across the ten colleges auspiced by Good Samaritan Education.

“It was a massive change in direction in my life and one I’ve always been grateful for,” Malarndirri says of her time at St Scholastica’s.

“It gave me the opportunity to explore a world far bigger than my own and I do look back on my time there as an important defining of character for me, not only as an Aboriginal woman but as a woman of faith.

“But it was an incredibly difficult time, if I reflect back on it. It required adjustment and support. And when I think of the people who supported me all the way through, and beyond, it’s amazing.”

That support was both academic and pastoral and, in Year 12, it included encouragement by a teacher to apply for a cadetship under the ABC’s Aboriginal Journalist Cadet Program.

“My first reaction was to laugh,” she recalls. “But then I did write a letter of application to the ABC, I was called into interviews and I got the job. I spent the next 17 years working at the ABC.”

Malarndirri later represented the seat of Arnhem in the Northern Territory Parliament for the Australian Labor Party and has now returned to journalism, working for SBS TV’s National Indigenous Television (NITV).

In addition, Malarndirri gives back to indigenous education by working part-time in the First Nations Cross Cultural Program at St Ignatius College, Riverview.

“My time at St Scholastica’s taught me how to share the learning of both these worlds, and I do that at Riverview,” she says.

Annie Barnett, Director of Boarding School and Indigenous Students at St Scholastica’s, says the school is very proud of Malarndirri, who was head girl in 1988.

“She’s a wonderful success story and a strong supporter of indigenous education,” Annie says.

St Scholastica’s has an association with indigenous students which goes back decades, thanks in large part to its proximity to the Redfern Aboriginal community and strong links with community leaders such as ‘Mum Shirl’ and Father Ted Kennedy.

“We’ve had two indigenous head girls over time,” Annie says.

There are currently 60 indigenous girls enrolled at the College, both as boarders and day students, with some coming from as far away as Yirrkala and Elco Island in Arnhem Land. Many of the indigenous students are on scholarships.

Annie says there are challenges for the students and for the school, with distance from home being one of the biggest difficulties.

“Certainly the distance from home is a very, very big challenge for the students from the Northern Territory, although critical mass helps. They’ve got each other.

“But it’s not always successful. A student from Cape York returned home because it just wasn’t working for her.

“One thing we have learnt over the years is that partnership with home is crucial to success. Parent support is vital and the leadership of the school has to be totally behind it too.”

Annie says experience has shown that no one program fits all when it comes to indigenous education and pastoral care.

“You have to be able to be flexible and to understand where they might be coming from,” she says. “For example, some of our students are living in a constant state of grief. They hear news regularly from home of suicides and deaths of cousins, school mates and family members.

“So, we do expect them to achieve goals and do well, but we have to realise that their needs are not always the same as non-indigenous students.”

As with all the Good Samaritan Colleges, indigenous culture is imbued in everything St Scholastica’s does, from the flying of the indigenous flag every day to Sorry Day celebrations, acknowledgement of country at school events and an indigenous perspective running right through the curriculum. An indigenous dance group performs at events like the opening-year Mass and speech nights, as well as external community events. There are sports and arts programs on offer, and supported learning groups tailored to individual needs are available to all students in the school. Special attention is also paid to pathways to work, study and traineeships. The girls are able to join other students of Good Sam Colleges in an immersion trip to Santa Teresa in Central Australia, where the Good Samaritan Sisters minister.

An equally outstanding reputation for excellence in indigenous education means that in Brisbane, some indigenous students travel up to two hours each day to attend Lourdes Hill College.

Formerly a boarding school, with historic links to indigenous communities across Queensland, Lourdes Hill now only takes day students, with some of its 26 indigenous students coming from North Stradbroke Island.

Cathy Hains, Head of the Faculty of Differentiated Learning, says the College has two key focus areas for indigenous education: in-class support and reconciliation.

“We have a very strong focus on supporting students in their studies and in helping them get into good post-school pathways,” Cathy says.

“Many of our students now go on to university and are studying wonderful things, while others take up traineeships or other opportunities and are doing really well.”

Students can take part in enrichment opportunities such as leadership camps, immersion trips to Santa Teresa, and visits to local cultural sites, like those on North Stradbroke Island.

Mindful of the Commonwealth’s commitment to halve the gap between indigenous and non-indigenous students in reading, writing and numeracy by 2018, focus areas at Lourdes Hill College include literacy, numeracy and other academic outcomes, pathways and transitions, cultural and pastoral activities, and building authentic partnerships between students, families and the College community.

“In all of this, we work very hard at ensuring that there is no sense of stigma or difference experienced by our indigenous students,” she says.

One of the ways that this is achieved is by the school-wide focus on reconciliation.

“We have a reconciliation captain, who is sometimes an indigenous student and sometimes not, as well as a reconciliation action group called STAR (Santa Teresa and Reconciliation),” Cathy says.

“It’s all about working together to achieve reconciliation,” Cathy says. “As a school community, we can’t change what’s happened in the past, but we do look to what we’re going to do in the future.”

Lourdes Hill employs an Indigenous Education Co-ordinator, Indigenous Support Teacher and is honoured to have local elder, reconciliation advocate and Lourdes Hill ex-student, Aunty Joan Hendriks, as Elder-in-Residence.

Aunty Joan, after whom one of the school’s houses is named, attended the school in 1949-50 and says her role as Elder-in-Residence is essentially an advisory role and one of companionship and mentoring.

“It’s such a joy being here,” she says. “The focus on reconciliation here goes with the ethos of the whole place – the Good Samaritan thing of ‘doing likewise’, reciprocity.”

Aunty Joan meets with the indigenous girls once a fortnight, takes both students and teachers on cultural excursions and immersion days, and is also part of the school’s Faith and Mission Team.

“One of the challenges is that not all of the girls are on the same page with their indigenous identity and some choose not to identify as indigenous at times,” she says. “But I try to encourage them to be real about who they are and to be an ambassador.

“We have to allow the young ones to learn more about their rich heritage – that we have the oldest living culture in the world and that they are going to be the future custodians of the story and the songlines.”

Connecting indigenous students with their culture is also a key priority for St Patrick’s College, Campbelltown, where 24 indigenous students are currently enrolled.

The school has recently employed an indigenous teacher, Tanya McEwin, who creates opportunities to connect the indigenous students with local elders and culture.

Apart from injecting an indigenous perspective into all curriculum areas, all Year 8 students at St Pat’s undertake Aboriginal Studies as part of their Human Society and Its Environments course. Next year, Aboriginal Studies will be further offered as an elective for older students.

“We’re having more girls identify as indigenous and explore their culture, which is wonderful because a lot of the girls from this area are not so connected to their culture,” says Acting Principal, Cecely McGeachie.

To assist this process, the school has an Indigenous Advisory Committee, which has elders from the local community who work with the school and the Aboriginal Educator to support indigenous culture at the College.

The indigenous students are offered opportunities including traditional dance, excursions to the Blue Mountains to see important cultural sites, forums featuring indigenous women talking about their experiences, and participation in camps for mothers and daughters to build relationships and connection to culture. The whole school community celebrates events such as NAIDOC Week, where a traditional smoking ceremony is held.

“We’re looking to build strategies and support for our girls all the time,” Cecely says. “And we’re also seeking to empower them. For example, we are developing a program of empowering our senior students to have a leadership role with our middle school girls.”

Other Good Samaritan Colleges have a smaller indigenous student population, perhaps of only a few students, but each school is committed to supporting the individual needs of students.

Nowhere is the individual approach more apparent than at Mater Dei School in Camden, NSW, a school for students with special needs which also incorporates an early intervention program.

“We celebrate indigenous culture here in our own Mater Dei way,” says Director of Development, Debbie Gates.

“Every student at our school has special needs and has their own individual service plan drawn up,” Debbie says. “So we are aware of each family’s needs in a more intimate way and that includes our students who identify as indigenous.”

The early intervention program has eight children identifying as indigenous, while the school has three indigenous students plus an indigenous teacher, and includes Aboriginal studies in its languages syllabus, with a particular focus on song and stories, such as the Rainbow Serpent.

“We also have visual cues throughout the school. For example, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flag flies at the school entrance and is presented at each assembly. We have various artworks throughout the school and we’re currently in discussion about commissioning an indigenous sculpture for the school foyer,” Debbie says.

“Where there is the opportunity, we will incorporate an Aboriginal context into liturgies or ceremonies and have those students who identify as indigenous take part in those activities.”

On a practical level, the staff at Mater Dei helps families to access funding that they might be entitled to and advocate for them in various ways.

That important link between school and home is also maintained at Santa Maria College, Northcote, in Victoria, where Pastoral Care Worker and Good Samaritan Sister, Glenys Dellamarta, is on hand to be a companion for students and families.

“I know our families really value her care and presence,” says Deputy Principal, Karen Rivalland. “We want our indigenous students, as with all our students, to feel well looked after, cared for and supported.”

That support includes having a Koori Education Worker, employed through the Catholic Education Office (CEO), who acts as the indigenous students’ advocate and helps them to be involved with events in the school, such as Sorry Day. The indigenous students take part in CEO initiatives which help put them in touch with their culture.

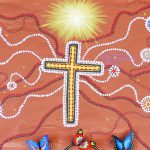

Santa Maria encourages students to take part in the Central Australian immersion experience led by Jungala Enterprises, which links the students with the land and its people. The school has this year ordered indigenous crosses from Santa Teresa to be blessed by a local elder and placed in all class rooms. It also has an indigenous garden. Local elder, Delise Lillyst, is a regular and very welcome visitor.

“We want to both support our indigenous students and grow the understanding of indigenous culture throughout the whole school,” Karen says. “It’s a journey of learning and valuing our indigenous culture that we value and definitely want to develop further.”

Making connections with other schools, tertiary institutions and indigenous bodies is crucial to the indigenous education strategy at St Mary’s Star of the Sea College in Wollongong, NSW, where seven indigenous students are enrolled this year.

“We work with the local Christian Brothers school in the area who have a larger cohort of indigenous students,” says teacher Ann-Maree Biddle.

“We hold a social justice day with them and invite them on some field trips, such as an outing to the Royal National Park with a local Aboriginal elder to see rock art.

“We also keep an eye out for any indigenous theatre that is on offer in the community and attend any relevant exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art and the Australian Museum in Sydney.

“Many of our indigenous students are very artistic and, together with Queensland artist, Sally Harrison, they have created a mural for the school depicting local sites of indigenous significance.”

The indigenous students meet together once a month and hear inspiring guest speakers. One of the school’s houses is named after distinguished Daly River artist and educator, Miriam Rose Ungunmerr–Baumann.

For colleges with a small population of indigenous students, the focus is on supporting the students within the context of the broader school community and helping them to access extra programs or initiatives in the local community.

Mater Christi College, Belgrave, in Victoria, has three indigenous students enrolled who are assisted through special funding from the Melbourne Catholic Education Office, allowing the school to focus on providing academic and pastoral support as needed.

“This year we also want to incorporate an indigenous mentor, and tutoring,” says the school’s International Student Co-ordinator, Jennifer Lee.

“We do encourage our students to take part in the different programs that are offered by local universities and other institutions aimed at encouraging indigenous students to go on to further study. They also take part in a camp for indigenous students.

“We try to be as supportive as we can for these students and also to focus on general awareness-raising of indigenous issues both in the formal curriculum and in other activities.”

A small group of students have identified themselves as indigenous at Mount St Benedict College, Pennant Hills in NSW, where the whole school has a focus on indigenous culture, both in social justice activities and across the curriculum. In addition, the indigenous students are able to take part in specialised opportunities of cultural significance if they choose.

Teacher, Paul Lentern, says local elders from the Darug Nation come to the school for important events such as Sorry Day, and a team of students last year travelled to the United States and took out the International Problem Solving Competition in which they focused on exploring Darug culture and finding better ways to respond to it.

Paul says that with such a small indigenous student population, identifying individual opportunities is the key.

“We had one girl who has expressed to us strongly that she wants to investigate and understand her indigenous heritage more and we have worked with her to identify and engage with other indigenous people,” he says.

Year 11 student at Rosebank College in Five Dock, Sydney, Sophie Campbell, is also exploring her indigenous identity after her Dad recently found that his family heritage was indigenous.

Sophie was exposed to indigenous culture further at Easter this year when she took part in the immersion trip to Santa Teresa.

“It was a really good experience,” she says. “Santa Teresa opened my eyes to how Australia began and what the Aboriginal people believe and it was so much more spiritual than here in Sydney.

“It’s one community up there and they all help each other and live together. They all look out for one another.

“It really broadened my knowledge about where I come from, in terms of being indigenous, and gave me a stronger connection to the Aboriginal people. Some of the women out there even identified me as Aboriginal from just looking at me which was really good.”

Sophie says she appreciates the commitment to supporting indigenous culture at Rosebank College.

“There are only a few of us at the school who do have an Aboriginal background,” she says. “But the school is really supportive. They acknowledge that we are indigenous and people look up to me in the school because of that. It feels good.”