The age-old spiritual process of discernment differs from most decision-making processes in two significant ways, writes Garry Everett.

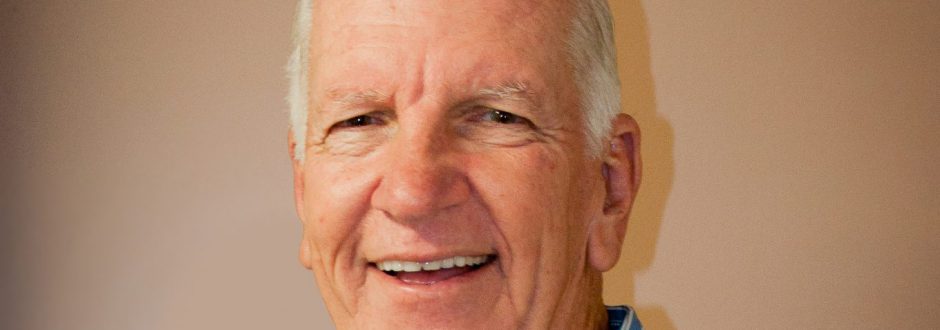

BY Garry Everett

Locally, I am referred to as “the old man and his dog”. It is an affectionate identifier, used by those not yet on a first name basis. Happily, as one fast approaching 80, it’s good to know that the word “doddery” has not been included. We two, Kiddo the nine-year-old cocker-spaniel and I, walk everyday through the preserved plots of native gums and other trees, past the man-made lakes, stop at the coffee shop near the water, and move on home past the small bustling shopping centre. I stop here and there and talk to all and sundry, while Kiddo seeks to look into all the nooks and crevices, and to play with other dogs.

During my chats, I listen attentively to the topics of conversation: local developments; the difficulties of “making ends meet”; raising kids; the NBN; Trump and Kim (most prefer Kath and Kim!). During the quiet parts of our walks, I mull over what I have heard, and reflect on my own changing thoughts on these and other issues. On arriving home, and while Kiddo drinks and finds his favourite place for a nap, I try to ask myself two questions. What is God saying to me about all this? And, what am I saying to God about the same issues? The second question is always the easier to answer.

I was reminded of this daily dog-walking and dialoguing experience when I recently joined the Good Samaritan Sisters from Australia, Japan, the Philippines and Kiribati for part of their 26th Chapter Gathering in Sydney – the part that focused on the preparation for articulating their Statement of Directions for the next six years.

Inviting some of their oblates and colleagues to be part of their Chapter was a first for the Sisters, and being invited was a first for me too. Not many males have had this privilege of trying to help set future directions for a religious congregation of women.

The Chapter process was impressive. For more than 12 months earlier, the Sisters, together with their ministry partners, oblates and associates, colleagues, volunteers, friends and family, had been involved in discussion groups, face-to-face and online, wrestling with emerging priorities to which they would commit hearts, minds and actions.

Out of all the possibilities, those present at the Chapter Gathering hoped to settle on a few which would create clarity of commitment, a sense of vision in mission, and a hope in a future better than our present. A Statement of Directions, identifying four key areas for mission emerged. It is a statement of which the congregation can be justly proud.

Achieving a quality result is always satisfying. However, for as long as I can remember, I have been interested in the processes by which that result is obtained. As a colleague/visitor I came to appreciate the skill of the planning team and the experience of the facilitators as they guided us through an age-old, yet constantly being refined, spiritual process, called discernment.

As a process, discernment differs from most decision-making processes in two significant ways. Firstly, discernment requires much more time of those involved in the process than other processes that depend on speedy resolutions. Secondly, discernment requires that the participants attend to the inspiration of the Spirit often detected in a prayerful, attentive, listening and contemplative mode.

In my own experience of using discernment, it is not the information-gathering, sifting, appraising and responding aspects that seem to be the difficulty. The real challenge is to be found in that first question I mentioned earlier: what is God saying to me/us about this? As we listen intently to ourselves and to others, we begin to notice the shifts, personally and communally, as the question takes us into the unfamiliar territory of the God of surprises.

Why unfamiliar?

A few Sundays ago, the Gospel parable was about the employer who paid those who worked the smallest number of hours the same as those who worked the longest. Many Catholics struggle with this parable, because on the surface the whole approach appears unfair or unjust. Even the explanation provided, which is about the generous nature of the owner/employer, does not seem to convince many. We are faced with those words of God: “My ways are not your ways…” Herein lies the most critical part of the discernment process as I understand it. We are not trying to discern what we think we should be doing, but rather what might be God’s ways.

Our friend, scripture scholar and exegete, Good Samaritan Sister Verna Holyhead has a beautiful reflection in her text Building on Rock where she says: “Like the disgruntled labourers in the parable, we are often inclined to look at life from our own limited perspective, so that ‘What’s in it for me?’ may be our uppermost concern, sometimes followed by envy when there seems to be more in a situation for other people than for me”. “As far as the heavens are above earth are my ways above yours…”, God reminds us.

The touchstone in communal discernment then seems to be how the group has explored whether or not God might respond differently from the collective wisdom emerging from the group. It might be useful to pay closer attention to the unpopular voice, the minority view, the dissenter. God was not in the mighty wind, but in the whispering breeze. Often throughout the Scriptures, God chooses a most unlikely person through whom to reveal God’s ways: Moses, Jeremiah, Jesus, Paul – and some might say today, Bishop Vincent Long of the Parramatta Diocese.

Perhaps many of us have not had the chance to experience the discernment process, either in our personal lives or in any group setting. Discernment is not a process required to decide whether to go to the hairdresser or to buy a new golf club. Discernment offers its greatest treasures when individuals or groups need to make significant decisions that will affect their lives and the lives of others, immediately and into the future. I was most appreciative of how it underpinned the individual and communal thinking of the Sisters and their colleagues during the recent Chapter.

One of my favourite authors, Old Testament scholar and Church reformer Walter Brueggemann, offers a valuable example of discernment at work:

“The Church is God’s agent for gathering exiles… First there are those exiles who have been made exiles by the force of our society… Secondly, exiles include those whom the world may judge normal, conventional establishment types. For the truth is that the large failure of old values and old institutions causes many to experience themselves as displaced people… It is not obvious among us how the dream [of God’s] well being for all, can come to fruition among us.”

As we reflect on Australian society, its changing values and fading institutions, how will we discern our way forward?