Good Samaritan Oblate Kathy Moran reviews Camino Skies, a movie which follows the journey of a group of men and women as they walk the Camino de Santiago. Questions arise around the modern context of the pilgrimage, dealing with grief and the value of companionship.

By Kathy Moran

Mention travel and you have my immediate attention. Mention Camino de Santiago and I am intrigued, as well as attentive. Why do I keep hearing of people who are training to ‘do the Camino’; who are just back from ‘doing the Camino’; who are going to ‘do the Camino’ for a second or third time? What is it about this pilgrimage that has called people since the ninth century and seems to be calling an increasing number of people in the twenty first century? Could any part of such a journey be for me?

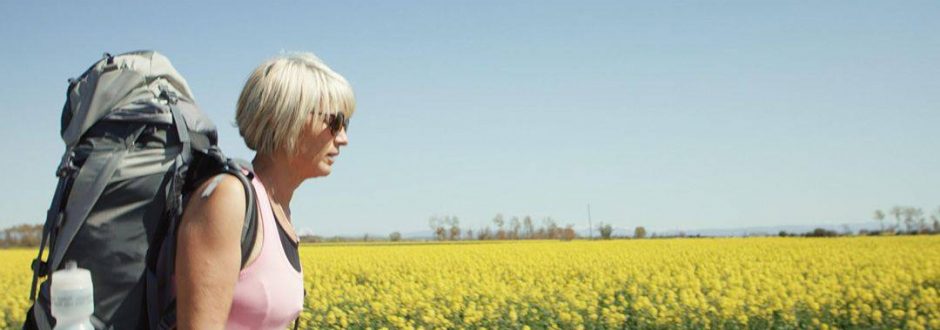

These and other questions, as yet unformed, preoccupied my mind as I recently previewed Camino Skies. The film follows a group of six New Zealand and Australian men and women, aged in their 50s to 70s, as they walk the 800 kilometre journey through Spain, en route to Santiago de Compostela. These pilgrims carry burdens –recent bereavements, specific physical ailments, consciousness of ageing. We see them trudging along muddy paths, in near freezing conditions. We see them ‘putting one foot in front of the other’, even when that is extremely difficult. We see them at breaking point, seemingly overwhelmed by their circumstances. We see them, against all odds, in full sun, passing wonderful vistas and glorying in their achievements. It seems a lot like life.

Camino Skies centres on companionship and the triumph of the human spirit over physical and emotional pain. It suggests that what is troubling can, in a sense, be ‘left behind’ on the journey and that a pilgrim can then walk with a new lightness. Those who have walked the Camino may well relate to this. The film shows those who might be contemplating such a journey that there is no shame in breaking down (at least temporarily) and that there are ways to make the journey somewhat less gruelling, such as hiring a car and driver to take them part of the way.

Throughout the film we see these pilgrims in the ‘refugios’ and taverns but we don’t see them in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, as we might have expected. Instead, the film comes to a close at the coastal town of Muxia, which, while admittedly spectacular, is not the Cathedral. It is almost as if, for this film, the Cathedral is incidental to the experience itself. This left me with more questions than those with which I began. Have journeys such as the Camino filled a modern need for a secular pilgrimage? Or have they become yet another trek through picturesque countryside? Is this how it was in the ninth century?

One of the more moving and spiritual parts of the film, for me, was a point along the way when a father-in-law took his son-in-law, with whom he was travelling, into a small old church. The older man shared with the younger that this was where he had asked a priest to say Mass for his family when he had done the Camino before. The son-in-law was then left in the church, alone, with his thoughts and, perhaps, with his God? This was one of the more powerful scenes in the film and, overall, the film would have benefited from the inclusion of more of these spiritual moments.

For me, the film had a rather one sided portrayal of grieving. It seemed to suggest that the way to deal with grief is physically, in the public eye, where there is always a ‘hugger’ who materialises at what she believes is the right moment, or who knows ‘exactly how you feel’. We seldom see a pilgrim in his or her ‘inner room’, finding solace in music, in meditation, or simply, in being.

Although I have friends who have done the Camino and found it a moving experience, I have always questioned whether the journey may be for me. The truth is that the film Camino Skies hasn’t inspired me to join the thousands of pilgrims walking the road to Santiago de Compostela. Predominantly, I believe I am already on my pilgrimage, seeking God through trying to live a balanced Benedictine life.