The Good Samaritan of the parable – a most unlikely hero – has the courage to see, the courage to feel, and the courage to act, says Good Samaritan Sister Sonia Wagner.

BY Sonia Wagner SGS

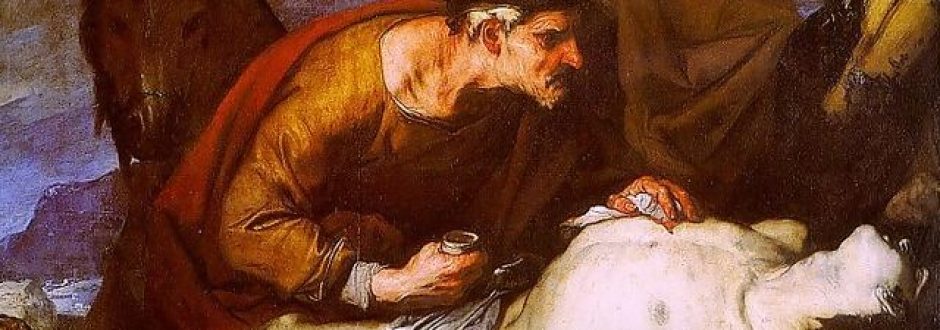

As I reflect on the parable of the Good Samaritan from the perspective of courage, I invite you to turn your gaze on Luca Giordano’s 1685 painting of “The Good Samaritan”.

Notice the anger on the face of the Good Samaritan; a brow furrowed with concern; a strong right hand almost fiercely clutching the oil or the wine; his left hand gently and compassionately tending the wound. Attend to the prone figure of the wounded man, the pallor of near-death, writhing and contorted in pain. By contrast, notice the patient face of the attendant donkey waiting to play a part in the next stage of the healing journey.

According to St Augustine, “Hope has two beautiful daughters. Their names are Anger and Courage; anger at the way things are, and courage to see that they do not remain the way they are”.

Aung San Suu Kyi, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991, led the non-violent movement for democracy in Burma (Myanmar), which she describes as a revolution of the spirit – a threefold way of compassion (Aung San Suu Kyi, The Voice of Hope, Conversations with Alan Clements, London, 2008). Suu Kyi sees compassion as always aligned to courage. To live compassionately is to courageously see the connection between ourselves and others, especially those who suffer; “the courage to see, the courage to feel and the courage to act” (pp.11-12).

The Good Samaritan of the parable – a most unlikely hero – has the courage to see, the courage to feel, and the courage to act. Jesus issues the challenge then to all of us when he concludes with the injunction – the punch line if you like – “go and do likewise” (Luke 10:37). This is a strong, direct exhortation to courage.

I want to share an Australian Good Samaritan parable of anger, courage, compassion and transformation recorded in the memoirs of Sister Dorothea Hanly (1871-1952)* and held in our Good Samaritan Archives.

“The story is told about a lad who was an orphan. He was sent to people who treated him badly so when he was about 14 years of age he ran away from them and wandered about the bush tired and hungry, till he met some men… These men were bushrangers, but he did not know then. When he was about 19 years of age, these men had a fight with the police and a policeman was shot. Some of the bushrangers were captured and this lad among them. They were tried in court and the bushrangers declared that the young man shot the policeman. He denied having fired a shot at all; he had a gun or pistol but did not use it. The evidence went against him and he was condemned to death. The others got long sentences but not death.

“When he heard that he was to be hung he refused to eat at all, was like a caged wild beast and cursed and swore at everyone. He said he would starve to death and not be hanged. Enter: The Good Samaritan Sisters, who formed a resident community at the Parramatta orphanage in 1859, visited the Parramatta prison every week, more often when it was necessary.

“One day Sister Gertrude Byrne came on prison visitation while this man was awaiting his execution. (Sister Gertrude was the youngest of 12 children who came from Tipperary Ireland to Sydney with her family. She entered on January 6, 1857, aged 19, the youngest of the original group to enter the newly forming congregation. In 1859 she was sent to the Parramatta orphanage where she taught the girls.)

“When the Sisters enquired about the prisoners, the attendant did not tell them of the young lad, thinking he was too violent for them to be allowed to visit. Something prompted Sister Gertrude to ask were there no more, was that really all? The keeper said, ‘There is another, Sister, but he is too violent, too unruly for you to see’. He then told her about the poor young fellow only 19 and how he felt about being hung, his refusing to eat, his bad language in his paroxysms of rage. She implored to be let see him. Of course she won the day; she always did, no one could refuse her when she pleaded.

“They brought her to the poor man; she talked to him but at first he refused to listen, just sulked. He never spoke a word. She begged him to take a little food, at first he refused, would not. She promised she would come every day to see him but that he must take some food. He did that evening when the keeper brought it to him. He never spoke but just took it very quietly, no violence at all. Next day, true to her word, she came bringing him a chicken and some nice things she had cooked for him herself. He ate what she brought.

“He spoke to her and she told him that she was going to get a reprieve for him. They were all praying for him and she would do all she could for him. Sister Gertrude then set about getting his sentence of death withdrawn. She appealed to the Governor and Premier and other influential people and it was altered to life. The poor fellow was so grateful that he did all in his power to show how much he appreciated the favour by behaving himself well and advising the other prisoners to do likewise.

“His influence with the prisoners was wonderful and he was a great favourite with them. His keepers could trust him without fear of being betrayed.

“Sister Gertrude kept up the contact, instructed him and he became a fervent Catholic. His conduct was so exemplary that he could be trusted with the care of the others, of the tools and the animals… He was given his freedom. He could leave the gaol, go where he liked but he said, ‘I know no other home. I shall remain here’. He was given charge of the garden. He made it his study and it was always in perfect order. He remained there until his death, faithful to his religion and his work.”

Good Samaritan stories abound. You would have your own experiences to relate. What is our Good Samaritan call “to go and do likewise”? I wonder if, like me, you sometimes feel reluctant to take up that call? Could it be narrow self-interest or the fear of what might happen to me if I reach out that prevents us? Or perhaps seeing too much, being overwhelmed by the complexity of what needs to be done in our world but in our own lives, too, that renders us paralysed and powerless?

Aung San Suu Kyi returns again and again to the profound simplicity of compassion. She uses the analogy of the pressure cooker that explodes in the kitchen sending soup everywhere – all over the ceiling and walls. You may feel paralysed. Where do you begin you ask? How is this mess ever to be cleaned up? Her advice is “don’t just stand there despairing, do something!” Start with the most obvious and the way will unfold (Aung San Suu Kyi, The Voice of Hope, Conversations with Alan Clements, London, 2008, p.124).

The legendary Australian actor, Bud Tingwell, has some wisdom to offer in regard to the courage it can take to respond to a call. He was asked why, towards the end of his life, he so often took up bit parts involving very brief appearances with few lines to speak. His response was – “well, you have to be very careful about what you refuse. What I aim to do is lower my expectations and raise my standards”.

So let us pray and support one another in taking up the Good Samaritan call to have courage; “the courage to see, the courage to feel and the courage to act”, and be encouraged by the words of Yahweh to Joshua when he is taking up a new role of leadership after the death of Moses: “Be strong and courageous. Do not be afraid; do not be discouraged, for the Lord your God will be with you wherever you go” (Joshua 1:9).

This is the edited text of an address Sister Sonia Wagner delivered on July 9, 2017 during an event at Lourdes Hill College, Brisbane, to celebrate 160 years of Good Samaritan life and mission.

Editor’s note: Sister Dorothea Hanly’s obituary says that “Her memoirs in note books and diaries give an excellent historical glimpse into the work and personalities of the early sisters and their life in the convent of the nineteenth century. There is considerable oral history surrounding Sister Mary Dorothea Hanly but her actual writings provide much archival data for the benefit of the following generations”.