Australians are good at responding to national emergencies with neighbourly deeds, but where is our compassionate response to the asylum seekers and refugees living on our shores, asks Congregational Leader Sister Catherine McCahill.

Summer in Australia evokes a kaleidoscope of experiences, emotions and memories. End-of-year fatigue, holidays, Christmas, parties and time away from work come readily to mind. Droughts, rain, floods, bushfires, cyclones are all part of the landscape.

This land that I call home is a continent of extremes, and summer is the most extreme. We recite and sing these words of Dorothea Mackellar:

I love a sunburnt country,

A land of sweeping plains,

Of ragged mountain ranges,

Of droughts and flooding rains.

I love her far horizons,

I love her jewel-sea,

Her beauty and her terror –

The wide brown land for me!

While all of us might not have experienced the “terror” of this land, we know of it. This summer has been no different. While parts of the country burned with out-of-control bushfires, other parts were devastated by cyclones, storms and floods.

Over recent weeks, as I have watched and listened to the media reports of these unfolding events and their aftermath, I have been thinking of the thousands of Australians who volunteer to assist in so many ways at this time.

An army of volunteers serve the community in state emergency services and various rural fire services. Ordinary women and men take time away from their regular lives to prepare the community, to fight the fires, to rescue and evacuate those impacted by flood waters, to clean up fallen trees, torn-down roofs and other debris, and to provide emergency accommodation. Above all, these generous neighbours provide a safety net and a reassurance that everyone will receive the help they need until they are safe.

Australians are good at this. We respond to crises with neighbourly deeds. We don’t ask about the credentials or background of the impacted person or family; we just roll up our sleeves and help.

And yet, we don’t always act this way. I am thinking of the asylum seekers and refugees in the Australian community who live with visas called Bridging Visa E (BVE). They are not in detention, but they are not eligible to receive much support – no housing, no healthcare, no work rights and no study rights. Thousands of people (more than 10,000 according to the Refugee Council of Australia) remain in this situation.

Many Australians are probably not even aware of their existence. Many who are aware remain silent about their plight. I ask myself, why don’t we respond? Why isn’t there an outcry about the injustice of their situation?

Sectors of our community, for example aged care and agriculture, cannot source enough people to fill job vacancies. At the same time, in the same community, we have women and men who want to work and are not allowed to work. It does not make sense.

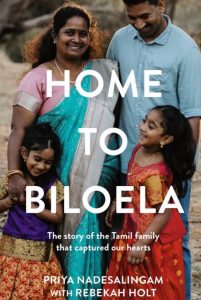

Over my summer break, my leisure pursuits – a book, Home to Biloela, and a film, One Life – challenged me to consider my own response to this parlous situation more deeply.

Home to Biloela: Allen & Unwin.

Home to Biloela, co-authored by Priya Nadesalingam and Rebekah Holt, relates the tragic story of Priya and Nades Nadesalingam and their Australian-born daughters, Kopika and Tharnicaa from 5 March 2018 to 10 June 2022.

At dawn on that March day, a contingent of Australian Border Force officials and police stormed the family’s small house in Biloela in rural Queensland and removed them to detention in Melbourne.

For more than four years, the family was detained by the Australian Government, our government, in various locations on the Australian mainland and on Christmas Island.

I wept and raged as I read of the brutality, the nastiness, and the cruelty inflicted on this woman, her husband and children. I was deeply moved by the courage and the kindness of ordinary women and men who fought for and supported them.

The family is now back in Biloela, attempting to heal the brokenness of those years. In large part this is due to the relentless pursuit of another kind; the people of Biloela kept fighting for their friends.

Bronwyn Dendle who led the initial charge explains why the people of Biloela were so upset: “Because we knew them, we worked with them, we loved them, we saw them everywhere.” Of course, there were other good people in Australia who joined the campaign and sustained it over many months and years.

The film One Life depicts events in 1938-39 in Czechoslovakia and Britain as Nicholas Winton undertakes the rescue and placement in England of nearly 700 Jewish children from the ghettos of Prague prior to the German occupation during World War II.

While on holiday from his stockbroker job, Winton visits his friend in Prague and is moved with compassion by the plight of the children. Together with three young Brits working for the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia, Winton plans and executes the rescuing and fostering of the children. His own mother and countless families in Britain provide the money (£50 per child for a visa) and a home for the duration of the war.

Early in the film, Winton meets his three British friends for a drink. When one of them says, “You have a lot of faith in ordinary people,” he replies, “I do, because I am an ordinary person.” Then each one of his friends echoes the same sentiment. So, from a group of “ordinary” persons active in Czechoslovakia and Britain, hundreds of Jewish children are saved from the Nazi concentration camps.

This book and this film remind me of the extraordinary things that ordinary people can do when they are personally confronted with human suffering, especially with unjust suffering.

It seems to me, that most Australians would be appalled at the injustice perpetuated on holders of BVE visas, if they encountered and had an opportunity to know such a person – woman, man or child.

So, if I am going to be a Good Samaritan, one who acts from “compassion which empowers hope” (SGS Statement of Directions), then I am impelled to speak up for these people on BVE visas, to amplify their voice, to cry out on their behalf.

I love this sunburnt country. How much prouder I would be if our kindness extended to all women, men and children living on our shores.