The pandemic has been an opportunity to practise the art of pausing to help us appreciate the beauty, the wonder, the mystery that is all around us, writes Judith Valente.

A friend of mine recently offered an interesting perspective on the challenges we face in the age of COVID-19. She said she no longer thinks of this time solely in terms of the pandemic, but as an opportunity for “pandeepening”.

Like many, I initially welcomed replacing my hectic pace with a more monk-like existence. I saw it as a chance to refocus on what matters most. Soon, though, new distractions and different whirlwinds of activity crept in. I spent more time connecting with others by smartphone and social media. Zoom meetings and webinars crowded my days.

Slowing down has never come easily. I often joke that I suffer from a dual diagnosis: workaholism and over-achieverism. The pandemic didn’t change that. Still, for several years now, I’ve been working intentionally at practising the art of pausing.

I realised I had to change when I was working as a foreign correspondent in London for The Wall Street Journal. I’d arrive at the office around 9am and proceed to read the news wires, get on the phone and begin reporting and writing my story for the day. I was fortunate to sit at a desk by a window that overlooked St Paul’s Cathedral. At some point, I’d look out the window and it would be dark outside. The day had passed, and I’d missed it.

I was like the narrator in a lovely little poem called Eyesight by the American poet AR Ammons in which the poet says:

It was May before my

attention came

to spring and

my word I said

to the southern slopes

I’ve

missed it, it

came and went before

I got right to see: …

The poet decides to travel farther north to where spring is not quite so far along, hoping to catch the first blush of the season. But he warns at the end of the poem:

It’s not that way

with all things, some

that go are gone.

Some things that go are gone. The poem became the wake-up call I needed.

The great spirituality writer and Trappist monk Thomas Merton once said that living a more contemplative life comes down to three tiny words: Now, Here and This. Now – living in the moment we’re in. Here – exactly where we find ourselves, with our mind on This – the one thing we are doing. Now. Here. This.

Can we challenge ourselves each day to pause – to remain silent, to clear the mind of concerns so that we can appreciate the beauty, the wonder, the mystery that is all around us?

Here are some simple ‘pausing practices’ that work for me:

In a wonderful series of guidebooks called Bridges to Contemplative Living, authors Jonathan Montaldo and Robert Toth discuss “writing a holy sentence every day with your life.” Each day, I try to write a three-line poem, a Japanese haiku. It’s hard to write a poem a day, but three lines, I can handle that. Three lines most people can handle.

Image: ACTA Publications.

It’s a meditation practice I learned from my friend Brother Paul Quenon, a monk at Merton’s monastery, the Abbey of Gethsemani. I find myself pausing periodically during my day, looking and listening for what will become my three lines. Writing those three lines always gives me a better sense of having lived the day.

In some ways, this practice resembles a tradition among African tribesmen who lead safaris. They stop periodically on the journey, and sit quite still, listening to the beating of the heart. They say they are trying to let their souls catch up with them on the rest of the journey. Sooner or later, we all have to let our souls catch up with the rest of our lives.

Weather permitting, I try to get outside each day, even if it is just to take a walk or gaze up at the moon and stars in the night sky. When it comes to walking as a spiritual practice, I’m in good company. The English writers Charles Dickens and CS Lewis walked several miles a day. So did the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard. “I walked myself into my best thoughts,” Kierkegaard wrote. There is even an expression in Latin, solvitur ambulando, it is solved by walking.

My Zumba fitness classes on Zoom are another form of pausing – a way of nurturing mind, body and spirit connection. Zumba is intensive aerobic exercise, but since it involves moving to pulsing Latin beats, it doesn’t seem like exercise. It’s more like dancing up a storm in my own living room, with no one else watching.

How else can we practice the art of pausing?

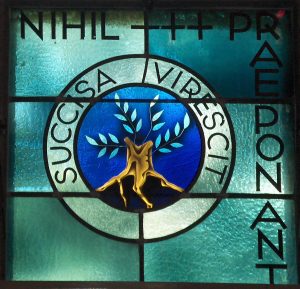

Image: Mount St Scholastica Monastery, Atchison, KS.

Whenever I return to Mount St Scholastica, the Benedictine monastery where I am an Oblate, one of my favorite places to visit is the vineyard. As any gardener knows, grapevines are wonderful plants. They’ll grow without much effort, but they need the careful touch of the vinedresser, who has to reach in several times a year and cut back the branches so that the grapes can receive the sunlight and nutrients they need. Too many branches dilute and dissipate what the grapes need to thrive.

There is a stained-glass window in the chapel at Mount St Scholastica that shows a branch rising from the earth with a few young shoots sprouting out of it. The top of the branch, however, has been cut off. Surrounding the image are some words in Latin: Succisa virescit. Cut back, it will grow stronger.

For someone like me, who is always running around, trying to do five things at once and be all things to all people, it’s a reminder to periodically slow down, to survey the grapevine that’s my life, and radically cut back on what’s non-essential, what’s not nourishing my soul.

And what is essential? That’s the big question.

I love the final scene from a film of the 1980s called Awakenings. It’s the story of a doctor, played by Robin Williams, who develops a drug regimen that reawakens patients who have been in a coma for decades.

Once conscious again, the patients revel in the most mundane of activities, like eating an ice cream cone, being read to, sharing a meal across a table with someone. They remind everyone on the hospital staff what a joy it is to experience the ordinary things of life.

Eventually, the drug wears off, and the patients slip back into their catatonic state. The doctor has to stand before his colleagues and report on what went wrong. He acknowledges that the drug failed, but says that what he learned from that failure was something far more valuable:

“The human spirit is more powerful than any drug. And that’s what needs to be nourished, with work, play, friendship, family. These are the things that matter,” he says. “These are the things we’ve forgotten. The simplest things.”

Succisa virescit. Cut back, it will grow stronger. Can we find the courage to cut back on what’s non-essential to nourishing our souls, and focus on what really matters, the simplest things?

In her book The Illuminated Space, filmmaker and Benedictine Oblate Marilyn Freeman describes her way of observing as an artist. It is very much like the slow mindful way we pray doing lectio divina, and it calls for pausing in four steps.

Read what the world is offering around you.

Reflect on what this is stirring inside you. What memories, thoughts, associations, insights, regrets, questions, prayers?

Respond. What is the invitation being offered? Is it to take action or to stop doing something? Is it to be more aware, to let go, to go deeper?

And then finally, Rest. Rest in silence.

All four practices help us to embrace the current moment.

At some point, theatres, sports arenas, pubs, restaurants, beaches, shopping malls, airports, and train stations will all be bustling again. This time of pandemic will seem like a distant memory. But the pandeepening can continue. Our pausing practices can continue. “The monastic heart resides within all people”, theologian and contemplative scholar Beverly Lanzetta reminds us. May that continue to be true.

This article is adapted from a talk Judith Valente gives as part of her series of retreats entitled ‘The Art of Pausing: Embracing the Current Moment’.